Why monitoring open science matters and how a global working group is mapping the way: Insights from OSMI Working Group 1

Nabila Salisu — Community Lead Global Partnership Coordinator, Open Science Community Nigeria, Nigeria & Julián D. Cortés — Principal Professor and Research Director, School of Management and Business, Universidad del Rosario, Colombia, Working Group 1 Co-chairs

Open Science is now central to science policy worldwide. Funders promote open access; universities encourage data sharing; governments call for broader participation, and communities are increasingly invited to co-create knowledge. Yet a critical question remains: how do we know whether these efforts are actually making science more open, more inclusive, and more useful to society?

Principles first

The Open Science Monitoring Initiative (OSMI) was created to tackle this question. OSMI focuses on building shared principles and practical guidance for monitoring open science, Specifically, Working Group 1 (WG1) has been tasked with a crucial first step: scoping the needs of the global community to understand what should be monitored, why, and for whom.

Existing efforts are fragmented. They often rely on inconsistent definitions often built on different definitions, and prioritize what is easy to measure rather than what matters most. This creates a real risk of reinforcing narrow conceptions of success and overlooking entire regions, communities, and knowledge systems that do not fit standard metrics.

WG1 approaches this challenge by starting from people’s needs. Co-chaired by Nabila Salisu, Community Lead Global Partnership Coordinator at Open Science Community Nigeria, and Julián D. Cortés, Principal Professor and Research Director at Universidad del Rosario’s School of management in Colombia, the group brings together perspectives from multiple regions, sectors, and disciplines to ensure monitoring reflects diverse realities rather than a single dominant model.

A framework for action

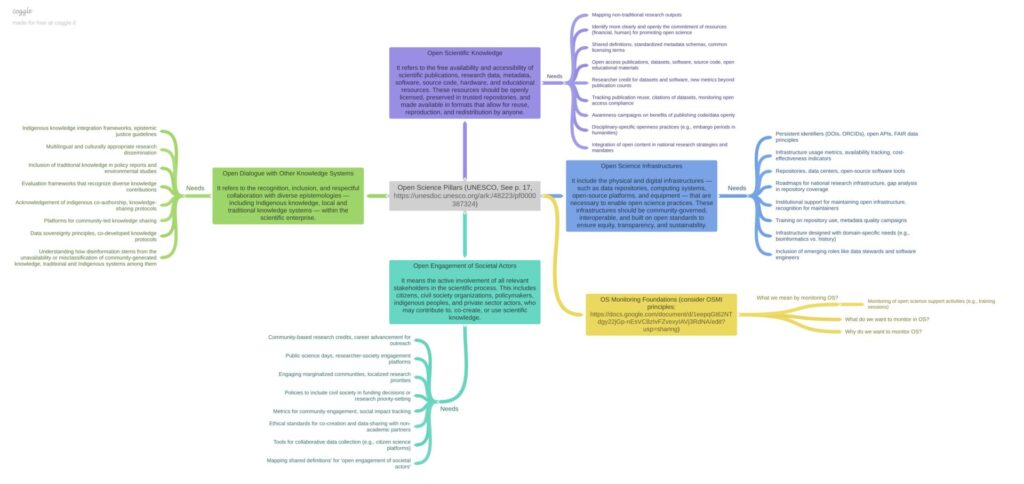

WG1 organized its scoping work around the four pillars of the UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science, complemented by a fifth cross-cutting dimension focused on monitoring itself. Together, these areas reflect where monitoring efforts are most urgently needed:

- Open Scientific Knowledge: Identifying non-traditional research outputs and developing shared metadata standards.

- Open Science Infrastructures: Establishing persistent identifiers and supporting FAIR-compliant data practices.

- Open Engagement of Societal Actors: Creating mechanisms to engage marginalized groups and assess the societal impact of scientific engagement.

- Open Dialogue with Other Knowledge Systems: Integrating Indigenous and local knowledge and promoting multilingual dissemination.

- Monitoring Foundations: Clarifying the purpose of monitoring and identifying who monitoring is meant to serve.

The figure below summarizes this initial mapping of Open Science monitoring needs across pillars and foundations (click here for enhancing image).

Listening to the Community

To ground this conceptual work in practice, WG1 conducted a targeted survey of 35 respondents, including repository managers, researchers, educators, administrators, funders, publishers, and Open Science coordinators. Respondents were geographically diverse, with Europe and Central Asia (31%) and East Asia and the Pacific (17%) representing the largest shares.

Beyond Open Access

The survey findings reinforce and deepen several key messages:

- Monitoring should support transformation, not just compliance. Respondents linked monitoring to research quality, public trust, societal impact, and reform of research assessment practices.

- Equity is central but under-measured. While Open Access remains a priority, respondents emphasized the need to monitor inclusion, benefit-sharing, and who benefit from Open Science policies.

- Structural barriers dominate. The most severe obstacles are institutional rather than technical, including lack of incentives and recognition, governance gaps, and sustainability challenges.

- Mixed methods are essential. Nearly all respondents supported combining quantitative indicators with qualitative evidence, expert judgement, and narratives to capture context and impact.

- Measurability remains uneven. Many “essential” indicators are only partially measurable today, highlighting the need for phased and adaptable monitoring approaches.

Looking ahead

The emerging picture from WG1 is that effective open science monitoring requires clear principles, agreed definitions, and collaborative processes that cut across regions, disciplines, and roles.

While the UNESCO framework provides a structured foundation for thinking about knowledge, infrastructures, and engagement, WG1’s work underscores that technical solutions alone are insufficient. Addressing deep-seated structural barriers, particularly incentives and governance gaps, is essential if monitoring is to support meaningful and inclusive openness rather than bureaucratic compliance.